The online food evolution still on a simmer – an appetizing case for Cloud Kitchens in Pakistan (1/3)

Author: Bilal Sheikh

“The two most important requirements for major success are: first, being in the right place at the right time, and second, doing something about it.” – Ray Kroc, Founder of McDonald

Over the past few months spent in fundraising, the usual culprit in causing investors a concern in the cloud kitchen space is the CAPEX-heavy nature of the business and how they’d prefer if it was an asset-light model.

Add to the mix the likes of “Seems like a difficult model to scale and maybe not worth the effort”, “Online food often burns a lot of money and customers are primarily discount-driven” and “But really, how big is the market?” and you’re well on your way to “Thanks Bilal for your time, but we’d like to come back to this later. Keep us posted”.

We do have some early commitments for our Seed round thankfully so we’re continuing the marathon, but I thought perhaps to publicly address these concerns to dispel the fears around investing in a cloud kitchen business and pave the way for a future where the Lettus team can solve for several important problems in the ecosystem.

As a reader, I hope that if you are convinced by the arguments below and possibly excited about what we’re building, you can re-share this article in your online circle/LinkedIn to help the team at Lettus get the word out.

Who knows, maybe our platform enables an entrepreneur to serve that incredibly good bowl of pasta in your neighborhood, all because an investor, who previously had some doubts, read your re-shared article and was excited about taking a bet on the team and idea.

Just maybe…

In any case, let’s start with the basics.

What’s a Cloud Kitchen?

A cloud kitchen is essentially a restaurant space without dine-in that is primarily used to cook food for online deliveries and/or takeaway. It can exist as a B2B model wherein you can rent it out to brands (Shared spaces) or you can cook on the brand’s behalf (Kitchen-as-a-Service).

If you’re running the kitchen to operate just your own brand, calling it a cloud kitchen may not be the right term to describe the business. You’re either then a digital restaurant or a full-stack dark kitchen player i.e. you manage everything from procurement to cooking food to deliveries.

There are more models out there but these are the primary ones.

Pros and Cons of operating a cloud kitchen

The pros of operating any of the models above are that:

- A much larger variety of online food options can exist in one single space (better optionality for customers in that area) whether that’s through your own portfolio or through a partner brand’s > more options, wider demand capture

- There are economies of scale for shared ingredients thereby enabling you to keep lower prices and provide better value to customers in the form of affordability

- Launch food concepts at a fraction of the cost to see what works and what doesn’t; literally just $500 (inclusive of R&D, consultancy, trials) or even less than this in emerging segments

- Have the flexibility to adjust to the dynamics of the market fairly quickly

- No front-of-house management, costs of ambiance/decor, or premium location rents

You’re extremely well positioned to respond to market trends when you have a lean and efficient cloud kitchen.

Are fried chicken and waffles getting popular? No problem. Conduct R&D at one kitchen and launch the product in the next 10 locations within a week. Ride 80% of the demand in that wave and then see if the dish sticks. If it does, great! Add it to all fast-food menus that operate in your kitchens. If it doesn’t, minimal harm is done (in fact you probably did make money if you executed properly so more as maximum profit done); move to the next dish. The flexibility that restaurant owners often don’t have (because of brand and menu limitations) probably won’t at scale unless they have an incredibly efficient supply chain and logistics interconnectivity i.e. your restaurant’s name is either McDonald or KFC.

The cons are that you’ll have to invest in building the kitchen. If you were on a B2C model you’d be looking for shared kitchen spaces as a start but there are only 5 of these kitchens that exist in all of Pakistan today (at least to our knowledge) and there are some major limitations to them. Then to grow, you’d have to work hard to maintain an online presence, understand and delve into digital marketing and social media, maintain a D2C channel or grow via the aggregator.

But all in all, the business is feasible, doable, and profitable; however, it requires a strong-willed, smart, and truly passionate group of people to figure it out and scale. In addition, the execution of this business model is also slightly more complex than your avg. startup because it has relatively more physical moving parts than say, a SaaS-focused company. In retrospect, the higher the complexity, the higher the barrier to entry so if someone does eventually scale the model, very few would be able to follow.

I’ll cover more on this in a follow-up article on Cloud Kitchen unit economics that addresses questions on burning, CAC, and LTV, what’s needed for a cloud kitchen business to succeed, and how to maintain food quality at scale for brands that do jump on board.

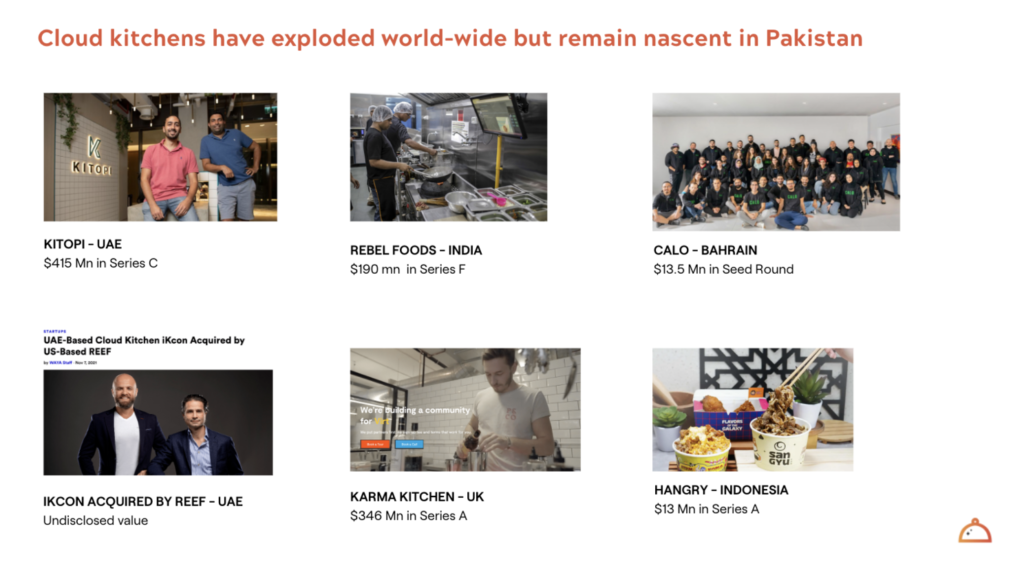

Side note: If you’d like to see a list of cloud kitchen operators who’ve done well in the space globally, you can view them here or see the quick snapshot below:

Now let’s get into the meaty part of this conversation from a VC standpoint.

Bilal, cloud kitchens are these bulky Capex heavy unsexy businesses. Isn’t there a cheaper way to operate this?

If you’re an investor reading this, bear in mind that the cost of setting up cloud kitchens varies in different countries and what might appear to be expensive in one part of the world, doesn’t necessarily have to be the same in other markets.

For example, a commercial kitchen in the US costs an avg. $300/sqft (source), Middle-East costs $175/sqft (source), India costs $30/sqft (source) and Pakistan costs $20/sqft (personal experience opening up 3 kitchens).

In other words, if you had to launch 100 kitchens of 1,000 sqft in the US, you’d need a whopping $30 — $35 Mn compared to maybe $3.5-$4 Mn in Pakistan. That’s about 90% cheaper!

$4 Mn for 100 kitchen sites…imagine the impact on the online food ecosystem!

Now granted that not all kitchens are created equal because every kitchen has different equipment requirements, different product lines, and also different standards, etc. The kitchen in the regulated market has to adhere to strict guidelines on operational and food safety and has expensive equipment and labor involved in the construction.

However, even while maintaining the standards in say a Pakistani cloud kitchen (the cost above $20k/kitchen accounts for all operational/food safety measures taken plus the cost of fixtures) the equipment and labor are essentially more affordable. The huge difference in cost is owing to kitchen equipment being assembled locally whereas, in other markets, the majority of the equipment is imported.

To put this in perspective, a 6-burner gas stove in the US costs between $4500 — $5000 (source). A 6 burner locally assembled in Pakistan that still makes the quality cut, performs the same operation albeit less efficiently, and can operate for 4 years or more if maintained, costs $500 — $720.

The comparison is mainly done keeping in mind that cloud kitchen scaling/expansion cost in Pakistan is significantly lower and therefore for the same VC $$ being plugged into a market, you’d get more distribution and access per $ spent in an emerging market than perhaps a developed one.

A case in point is India where cloud kitchens have boomed to the point where you now have startups acquiring cloud kitchen-first brands. This is mainly because the ecosystem saw investment that enabled multiple startups such as Rebel Foods who were able to build out 300+ kitchens across the country, then moved abroad to 6 countries and have now become a global unicorn. Curefoods, recently raised $62 Mn to become a Thrasio-like player for cloud kitchen brands. (source)

Bottom line, when you compare the amount of funding that has gone into cloud kitchen startups worldwide, it requires a fraction of that investment to achieve the same scale in Pakistan.

But isn’t there a more asset-light model?

Unfortunately, if you’re in the cloud kitchen business, there isn’t one. You either need to build out the infrastructure or you wait for someone to set up the shared kitchen spaces across the country and then just rent those out to operate your brands.

You can attempt the Taster model in Europe, which is to find under-utilized kitchens and give them brands to operate, but it requires an existing network of kitchens built with certain standards (which most kitchens in Europe are) before they can be utilized for scaling or at the minimum, requires food entrepreneurs to warm up to the concept of cloud kitchens before they entertain your menus in their premises as well as central kitchens of your own to make procurement, production and logistics easier for the brands who work with you.

In either case, the team at Lettus would rather be one of the early ecosystem builders because while there is room to operate 1 – 2 players building out a network of dark kitchens nationally, getting into a city first unlocks demand and reduces the attractiveness for competitors to open up another set of kitchens.

If we get to a critical mass of say 3–4 kitchens in each of the first 15–20 cities of Pakistan, it is highly unlikely that another player would come in and say “Let me launch 100 kitchens too!”.

So let’s conclude this bit with absolute clarity that if you’re getting your feet wet in the cloud kitchen space, it will require investment in Capex, albeit a moderate one, but once that’s done, it’ll remain and be long-lasting. Think of a cloud kitchen as sort of like a mini-mall.

A slightly different take on viewing a cloud kitchen investment

A mall is built keeping a 25–30 year+ horizon in mind (kitchens will obviously be less but this is to draw an analogy). The mall is maintained, kept running, etc and the tenants or brands inside the mall essentially change over time depending upon market dynamics and consumer preferences.

Imagine if you will that across the 100 sites across Pakistan, you can adjust the portfolio based on evolving consumer preferences in food, get popular products launched in multiple cities in 1/10th the time and effort, and give restaurants, chefs, and food entrepreneurs an actual opportunity at expanding into cities they’ve never considered before! Not to mention the data and insights into these cities which are largely unavailable to the public.

Finally, the CAPEX bit, in our perspective, will actually become a long-standing moat. This network of kitchens will stand the test of time and continue to play an active role in the online food ecosystem for decades to come or simply be acquired by an international operator (just like how REEF technologies acquired cloud kitchen player iKCon to expand from the US to UAE)…and still continue to play the same critical role. The acquisition is also to answer your question “What if someone comes in with a lot of money and tries to copy you?”, “What if Google does this?” 😉

Trust me, if you’ve built a kitchen before, it’s much easier to just acquire an existing player with a network than build it 10 times over…

Okay makes sense. But isn’t operating multiple product lines in a single kitchen expensive and complex?

Technically having a cloud kitchen operating multiple cuisines is in fact its biggest advantage and something worth figuring out at scale. However, the view of costs as being prohibitive for running a multi-cuisine operation might be skewed.

In Pakistan, 7 types of major cuisines dominate the online food scene. It’s the Pakistani and Continental cuisine, Chinese food, Pizza, Burgers, Fried Food (Chicken, Fries, etc.), and Desserts. Each has a hot or cold line of equipment that is the major differentiating factor.

Supporting equipment such as working tables, shelves, under-counter chillers, appliances, etc. are all common to every kitchen and not required to operate a single hotline.

So the question really is, what’s the cost of each of these cuisine lines?

- Pakistani and Continental > sub-segments include Biryani, Pulao, Gravies, BBQ, Tandoor, Roll Parathas, Breakfast, etc. ($1.5k – $2k)

- Chinese/Asian > sub-segments include desi Chinese food, pan-asian style ($1.25 — $2k)

- Fast food > Pizza, burgers (gourmet or smash), fried chicken (hard to find a no. 2 to KFC), fries, wings, snacks ($3.5 — $4k)

- Desserts > cakes, brownies, cookies, a mix of cold desserts ($1.5 — $2k)

- Beverages > shakes, juices etc. (<$500)

- International favorites> shawarma (Arabic or local), Mexican, sushi, wraps, salads and sandwiches etc. ($1.2 – $1.5k)

You can see how launching a section for any of the cuisines above is incredibly affordable relative to the same costs in other markets. The idea is to open a kitchen optimizing for the portfolio of brands by analyzing what’s required in a certain community. Often just 3–4 of the product lines from the above are needed to fill the gaps of food options.

Hmm. Tempting but what about the size of the market? I mean, how many restaurants or brands are really out there?

There are approximately 70,000 – 80,000 restaurants in Pakistan as quoted by Foodpanda’s CEO once in an interview. However, 95% of local and international restaurant brands, among these restaurants, are concentrated in just 3/200+ cities.

This represents a MASSIVE potential to scale brands into Tier 2-5 cities and better serve the customers there.

You don’t actually need a lot of restaurants or brands to make the cloud kitchen model work whether you’re on a B2C one or a B2B one. The number of restaurants problem is faced by shared kitchen space models that constantly require more/stable tenants to generate revenue but even they can overcome the revenue ceiling by providing ancillary services to help their tenants with procurement, last-mile deliveries, or kitchen-tech-related services; aspects which get more and more difficult to scale for restaurants with a small management team can be where the shared kitchen space operators add value. See Karma Kitchen which raised $324 Mn in Series A.

From our standpoint, if you’re in the B2C or B2B play, you need to focus on the product lines that bring in 80% of sales in online food and aim to guide the process whereby brands operate in your kitchen. What this means is that your research and analysis should demonstrate that product categories A and B will work tremendously well in the part of the city where your kitchen is set up but may not be suitable for category C.

If you’re setting up a cloud kitchen whether to provide Kitchen-As-a-Service (you cook on the brand’s behalf) or Shared Spaces (brands rent out the kitchen from you), you just need 3-4 partner brands/kitchen to scale. If that brand has the potential to be a city-wide sensation, you take the same 2–4 brands and scale them throughout the city, iterating based on customer feedback.

However, this is from a feasibility perspective, not a potential perspective. Potentially speaking, we can help 100s of brands and food entrepreneurs with an excellent Product-Market fit (PMF) to scale depending on where they make the most sense in our network.

For example, in our first kitchen in Islamabad, we discovered how Chinese food options in the community our kitchen was based in, were limited, not great in quality, expensive, and with questionable portions.

When the right Chinese food brand was launched through our portfolio, we hit 100+ online orders/day with bare minimum marketing in less than 2 months from one location! It’s still thriving and we’ve received raving reviews about the quality/affordability of our Chinese food 🙂 We’re now looking at how to expand the same quality across our entire network.

Now coming back to the community and market sizing bit. If you picture Pakistan as a collection of smaller communities within 6–7 KM radius (because this is as far as your kitchen can probably deliver), these communities would number more than 25,000.

Every community would have some gaps in terms of options. This gap can exist on the premise of food option (e.g. no dessert brand), quality (e.g. no good quality dessert brand), price (e.g. no affordable dessert brand), or a brand with equity (e.g. checks all 3 of the earlier attributes but isn’t a brand itself or has poor packaging, presentation, etc.)

How long would it take to have every one of these major options in every community of Pakistan?

Decades!

Your first reaction might be, that not every community needs every one of these options and yes, you’d be absolutely right. But every community does require some basic options and the gap right now is exceptionally wide.

How wide you ask? Well… Here’s a quick snapshot

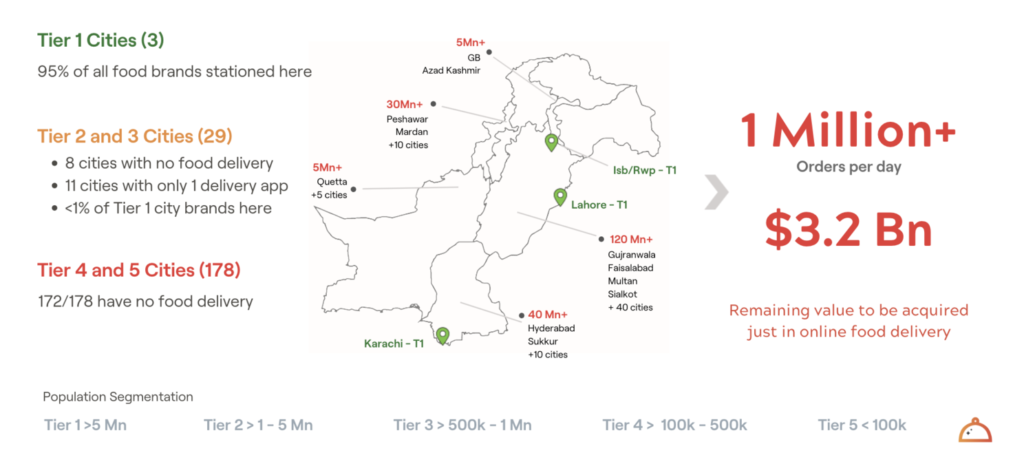

Takeaways from the dandy visual above:

- Cities are segmented based on population density (seen at the bottom of the visual)

- Tier-1 cities (Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore) get 95% or more of food brand action meaning the remaining 195+ cities in Pakistan are far away from ever getting great food options online in the near future

- Tier-2 cities (29): 9 with no food delivery. 11 with just 1 app. <1% of the Tier-1 food brand action here

- Tier — 3 cities and beyond: Mostly cut off from an evolving online food ecosystem

- Now consider that these cities are still far off from the optionality that’s available in Tier-1 cities. Hence there’s plenty of work to be done to provide access to better, more affordable food options without even beginning to optimize a portfolio per community.

A case in point is Peshawar. A bustling city of more than 2.5 Mn people and yet folks travel to Islamabad (a neighboring city 2 hours away) to eat out at brands/explore different product lines because very few of them have ventured or opened up in Peshawar itself. One of our landlords is from Peshawar so we have a good view on this.

A digital future without…online food?

If we’re imagining a digital future in Pakistan where consumers have optionality, digital services, and are engaged in e-commerce, food ordering is the absolute most basic service to be found online and possibly the very first, low-risk vertical to engage with.

170+ cities in Pakistan don’t have food delivery and 95% of all local and international food brands are concentrated in just 3/200+ cities in Pakistan

So if you don’t have decent food options when you finally made the effort to explore what you could order online, you’re leaving a large gap in the online customer experience.

Our hypothesis is that a consumer begins their online journey by purchasing basics such as Food, Fashion/Household (e.g. Daraz), Mobility Services (e.g. Careem), Entertainment Content (e.g. Netflix), etc. I’d include online grocery but that only took off in US 10 years after Amazon so probably not as fundamental. Then the consumer ventures into verticals such as fin-tech, ed-tech, health-tech, etc. Food is a low-risk way to come online and explore what’s available. Most of the folks around me who began using other digital services such as Airlift or Panda Mart started their journey with online food ordering.

Now that we’ve established the important role of online food, here’s an estimate of the size of the food economy and subsequently the size of the online food space.

Market Sizing from an end-consumer angle

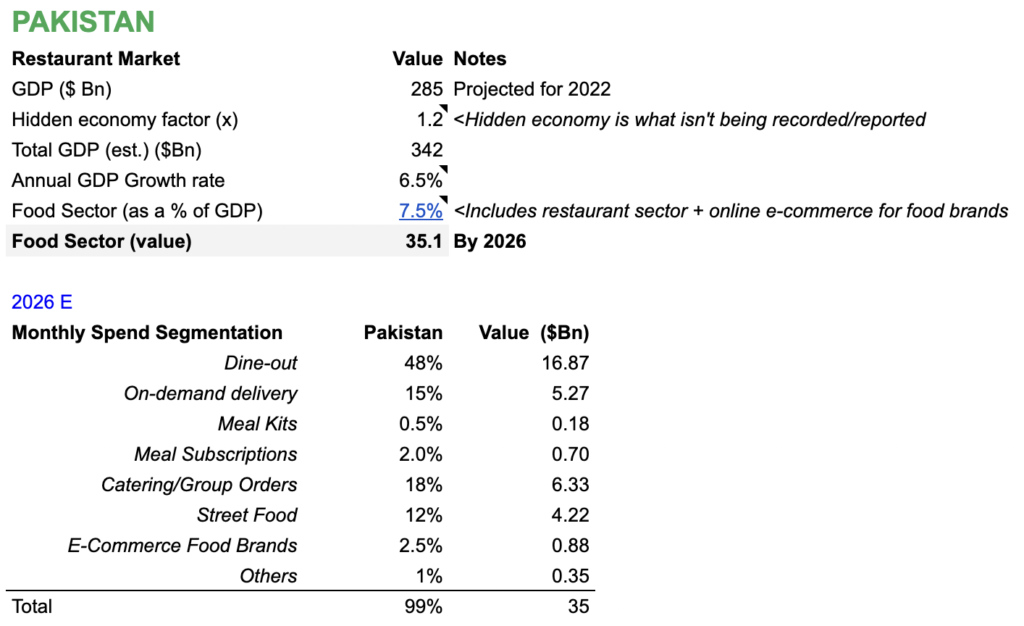

A few key points in the table above:

- The Hidden Economy factor is something applied to Pakistan because a large portion of the economy does not get documented. Conservatively we’ve kept this to 1.2x the reported economy’s size.

- The food sector is often 4–6% of the country’s GDP as analyzed for the US, Middle East, and Indonesia. We’ve kept a higher share of 7.5% to include undocumented street food sellers which are part of that economy and the thousands of entrepreneurs who are selling food products online through social media; again undocumented for the most part.

- The Monthly Spend segmentation are estimates and it’s hard to find data on them. But they are for the most part reasonable given an analysis of the US market and some Middle-Eastern reports on online food delivery. We’ll be honest here; the meal kits/subscriptions segment might be slightly overstated.

You’re welcome to critique the numbers/approach above but please do so as respectfully as possible. Trying to find/consolidate data in a country where there’s very little documentation and statistics is hard to do.

The Big Reveal

Now comes the exciting bit!

Aggregators (Foodpanda, Careem, and Cheetay) in Pakistan are collectively doing <180k orders/day (unofficial but highly reliable sources).

If the argument about Pakistan’s population is made where we have 220 Mn people etc., the estimated middle-class population is approximately 15–20 Mn.

Now bearing the following conservative assumptions in mind:

- 35% of the middle-class population engages with online food delivery (18 Mn x 35% = 6.3 Mn)

- Orders just 4 times a month at AOV of $3.5/order (RPU is $28/month)

You’re looking at 25 Million orders/month or close to 1 Million orders/day which is a potential from just the Middle-class. If aggregators are collectively doing <180k orders/day today, there’s about 80% of the online food delivery market that is still untapped or more than $3 Bn in consumer spending that can be brought online over the next 5 years.

Keep in mind that on average, we spend about 25 – 30% of our income on food every month. Over time, even more customers will shift to ordering online (especially Gen Z’s) and this portion of spending will be found on food delivery apps powered by cloud kitchens.

80% of the online food delivery market remains to be acquired

Note that the above isn’t farfetched in terms of order volume because we’ve assumed that online food delivery is only being engaged by a limited portion of the middle class. If food options become more affordable, you can tap into the next 30–40 Mn people who live in semi-urban cities too or if you play on experience and branding, catering to the top 5 Million who are potential power-users ordering more than 5 times a week.

Bottom line is that we’re still very early in unlocking Pakistan’s true potential in the online food ecosystem. What better way to unlock that potential than to give consumers food options that fit their spending pattern, addresses a clear need, and can become part of their daily lifestyle in the years to come?

In our next issue of this series, we’ll address some of the key problems cloud kitchens can solve in the online food ecosystem and go deeper into the unit economics of the business.

About Lettus Kitchens

The team at LK is on a mission to serve the world’s favorite food in every neighborhood and help food entrepreneurs unlock their potential.

We’re a Kitchen-as-a-Distribution (KaaD) platform operating a hybrid dark kitchen network. The hybrid part implies that some of these brands are our own and some are partners. Our partners work with us by either sending fully-prepared or semi-prepared food and we become the point for assembly and packaging, enabling better scalability. Customers can place an order via our aggregator partners or our website/mobile app powered by BlinkCo.

We’re onto our 4th kitchen, 3rd city, have completed more than 40,000 orders to date, and operate a portfolio of 8 brands.

We’re raising $1 Mn as part of a larger Seed round to accelerate the next phase of our growth to create a long-lasting impact on the ecosystem.

Let’s take Lettus Kitchens to the next level!

Above: The Lettus kitchen crew taking a day off to play cricket 🙂

Why do we call ourselves Lettus?

Because we’re a big fan of cheeky puns…

No seriously. That is one of the reasons. But the main one is that the name represents a philosophy (let us take care of everything for you) and each letter of the startup’s name represents one of the six flavors of food because we’ll be dominating the food space 🙂

The word Oleogustus? That’s the flavor of fat discovered in 2017 🙂